I'm not a surrealist. I just paint what I see. — Frida Kahlo

THE PAST AND THE PRELUDE

In his introduction to the classic novel Invisible Man (1952), ambiguous black and literary icon Ralph Ellison says the process of creation was "far more disjointed than [it] sounds ... such was the inner-outer subjective-objective process, pied rind and surreal heart."

Ellison's allusion is to his book's most perplexing character, Rinehart the Runner, a dandy, pimp, numbers runner, drug dealer, prophet, and preacher. The protagonist of Invisible Man takes on the persona of Rinehart so that "I may not see myself as others see me not." Wearing a mask of dark shades and large-brimmed hat, he is warned by a man known as the fellow with the gun, "Listen Jack, don't let nobody make you act like Rinehart. You got to have a smooth tongue, a heartless heart, and be ready to do anything."

And Ellison's lead man enters a world of prostitutes, hopheads, cops on the take, and masochistic parishioners. He says of Rinehart, "He was years ahead of me, and I was a fool. The world in which we live is fluidity, and Rine the Rascal was at home." The marquee of Rinehart's store-front church declares:

Behold the Invisible!

Thy will be done O Lord!

I See all, Know all, Tell all, Cure all.

You shall see the unknown wonders.

Ellison and Rinehart had seen it, but had no name for it.

In an introduction to prophet Henry Dumas' 1974 book Ark Of Bones and Other Stories, Amiri Baraka puts forth a term for what he describes as Dumas' "skill at creating an entirely different world organically connected to this one ... the Black aesthetic in its actual contemporary and lived life." The term he puts forth is Afro-Surreal Expressionism.

Dumas had seen it. Baraka had named it.

This is Afro-Surreal!

THIS IS NOT AFRO-SURREAL

A) Surrealism:

Leopold Senghor, poet, first president of Senegal, and African Surrealist, made this distinction: "European Surrealism is empirical. African Surrealism is mystical and metaphorical." Jean-Paul Sartre said that the art of Senghor and the African Surrealist (or Negritude) movement "is revolutionary because it is surrealist, but itself is surrealist because it is black." Afro-Surrealism sees that all "others" who create from their actual, lived experience are surrealist, per Frida Kahlo. The root for "Afro-" can be found in "Afro-Asiatic", meaning a shared language between black, brown and Asian peoples of the world. What was once called the "third world," until the other two collapsed.

B) Afro-Futurism:

Afro-Futurism is a diaspora intellectual and artistic movement that turns to science, technology, and science fiction to speculate on black possibilities in the future. Afro-Surrealism is about the present. There is no need for tomorrow's-tongue speculation about the future. Concentration camps, bombed-out cities, famines, and enforced sterilization have already happened. To the Afro-Surrealist, the Tasers are here. The Four Horsemen rode through too long ago to recall. What is the future? The future has been around so long it is now the past.

Afro-Surrealists expose this from a "future-past" called RIGHT NOW.

RIGHT NOW, Barack Hussein Obama is America's first black president.

RIGHT NOW, Afro-Surreal is the best description to the reactions, the genuflections, the twists, and the unexpected turns this "browning" of White-Straight-Male-Western-Civilization has produced.

THE PRESENT, OR RIGHT NOW

San Francisco, the most liberal and artistic city in the nation, has one of the nation's most rapidly declining black urban populations. This is a sign of a greater illness that is chasing out all artists, renegades, daredevils, and outcasts. No black people means no black artists, and all you yet-untouched freaks are next. Only freaky black art — Afro-Surreal art — in the museums, galleries, concert venues, and streets of this (slightly) fair city can save us!

San Francisco, the land of Afro-Surreal poet laureate Bob Kaufman, can be at the forefront in creating an emerging aesthetic. In this land of buzzwords and catch phrases, Afro-Surreal is necessary to transform how we see things now, how we look at what happened then, and what we can expect to see in the future.

It's no more coincidence that Kool Keith (as Dr. Octagon) recorded the 1996 Afro-Surreal anthem "Blue Flowers" on Hyde Street, or that Samuel R. Delany based much of his 1974 Afro-Surreal urtext Dhalgren on experiences in San Francisco.

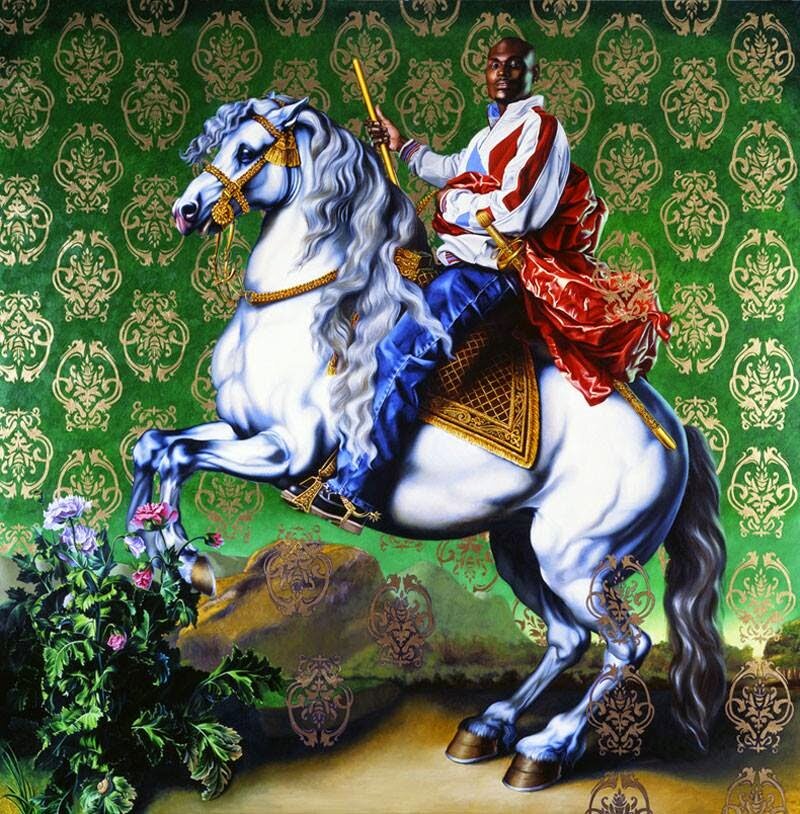

An Afro-Surreal aesthetic addresses these lost legacies and reclaims the souls of our cities, from Kehinde Wiley painting the invisible men (and their invisible motives) in NYC to Yinka Shonibare beheading 17th (and 21st) century sexual tourists of Europe. From Nick Cave's soundsuits at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts to the words you are reading right now, the message is clear: San Francisco, the world is ready for an Afro-Surreal art movement.

Afro-Surrealism is drifting into contemporary culture on a rowboat with no oars, entering the city to hunt down clues for the cure to this ancient, incurable disease called "western civilization." Or, as Ishmael Reed states, "We are mystical detectives about to make an arrest."

Prince Tommaso Francesco of Savoy-Carignano, Kehinde Wiley (2006)

A MANIFESTO OF AFRO-SURREAL

Behold the invisible! You shall see unknown wonders!

1. We have seen these unknown worlds emerging in the works of Wifredo Lam, whose Afro-Cuban origins inspire works that speak of old gods with new faces, and in the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who gives us new gods with old faces. We have heard this world in the ebo-horn of Roscoe Mitchelland the lyrics of DOOM. We've read it through the words of Henry Dumas, Victor Lavalle, and Darius James. This emerging mosaic of radical influence ranges from Frantz Fanon to Jean Genet. Supernatural undertones of Reed and Zora Neale Hurston mix with the hardscrabble stylings of Chester Himes and William S. Burroughs.

2. Afro-Surreal presupposes that beyond this visible world, there is an invisible world striving to manifest, and it is our job to uncover it. Like the African Surrealists, Afro-Surrealists recognize that nature (including human nature) generates more surreal experiences than any other process could hope to produce.

3. Afro-Surrealists restore the cult of the past. We revisit old ways with new eyes. We appropriate 19th century slavery symbols like Kara Walker, and 18th century colonial ones like Yinka Shonibare. We re-introduce "madness" as visitations from the gods, and acknowledge the possibility of magic. We take up the obsessions of the ancients and kindle the dis-ease, clearing the murk of the collective unconsciousness as it manifests in these dreams called culture.

4. Afro-Surrealists use excess as the only legitimate means of subversion, and hybridization as a form of disobedience. The collages of Romare Bearden and Wangechi Mutu, the prose of Reed, and the music of the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Antipop Consortium express this overflow.

Afro-Surrealists distort reality for emotional impact. 50 Cent and his cold monotone and Walter Benjamin and his chilly shock tactics can kiss our ass. Enough! We want to feel something! We want to weep on record.

5. Afro-Surrealists strive for rococo: the beautiful, the sensuous, and the whimsical. We turn to Sun Ra, Toni Morrison, and Ghostface Killa. We look to Kehinde Wiley, whose observation about the black male body applies to all art and culture: "There is no objective image. And there is no way to objectively view the image itself."

6. The Afro-Surrealist life is fluid, filled with aliases and census- defying classifications. It has no address or phone number, no single discipline or calling. Afro-Surrealists are highly-paid short-term commodities (as opposed to poorly-paid long term ones, a.k.a. slaves).

Afro-Surrealists are ambiguous. "Am I black or white? Am I straight, or gay? Controversy!"

Afro-Surrealism rejects the quiet servitude that characterizes existing roles for African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, women and queer folk. Only through the mixing, melding, and cross-conversion of these supposed classifications can there be hope for liberation. Afro-Surrealism is intersexed, Afro-Asiatic, Afro-Cuban, mystic, silly, and profound.

7. The Afro-Surrealist wears a mask while reading Leopold Senghor.

8. Ambiguous as Prince, black as Fanon, literary as Reed, dandy as André Leon Tally, the Afro-Surrealist seeks definition in the absurdity of a "post-racial" world.

9. In fashion (John Galliano; Yohji Yamamoto) and the theater (Suzan Lori-Parks), Afro-Surreal excavates the remnants of this post-apocalypse with dandified flair, a smooth tongue and a heartless heart.

10. Afro-Surrealists create sensuous gods to hunt down beautiful collapsed icons.

Lovesexy, Prince (1988)

AFRO-SURREALISM IN ACTION

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of the African Diaspora present the works of Mutu, William Pope L., Trenton Doyle Hancock, Glenn Ligon, Wiley, Shonibare, and Walker en masse, with Lam's Jungle as a center piece. Lorraine Hansbury Theater stages Genet's The Blacksand Baraka's The Dutchman, while San Francisco Opera adapts Aimé Césaire's Caliban and the Fillmore has an Afro-punk retrospective. Afro-Surreal adaptations of Reed's Mumbo Jumbo (1972), Hurston's Tell My Horse (1937), and Marvel's Black Panther will grace the silver-screen.

These are the first steps in an illustrious and fantastic journey. When we finally reach those unknown shores, we will say, with blood beneath our nails and mud on our boots:

This is Afro-Surreal!