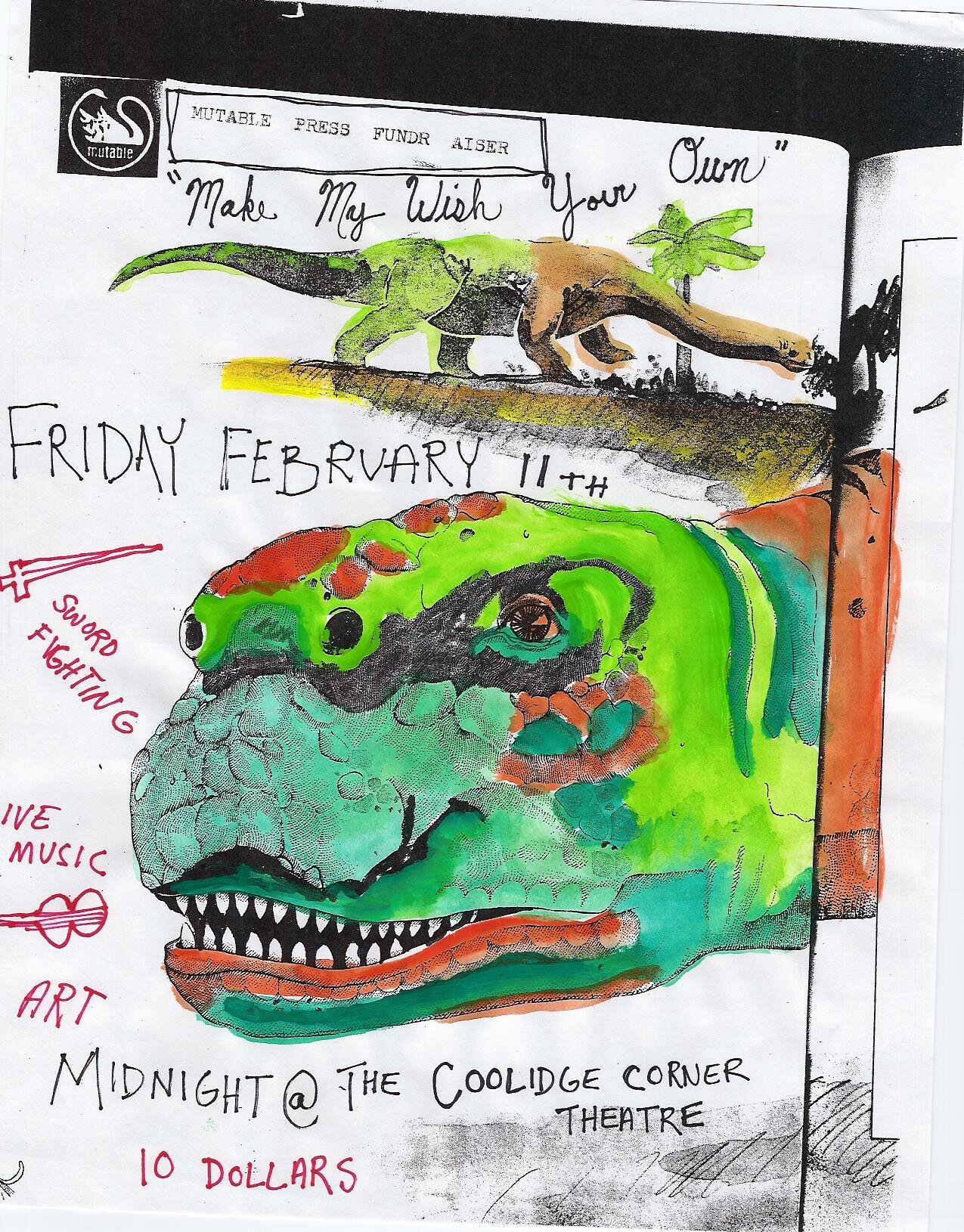

James Parker, Globe Staff

BROOKLINE!-It ain’t easy, moving and shaking. Gabe Boyer–28-year- old playwright, pamphleteer, neophyte impresario–stood alone outside the Coolidge Corner Theatre at 2 o’clock last Saturday morning, sucking on a moody cigarette. Inside, in the upstairs theatre, a performance listed in the evening’s program as “Noel Webber and the Giant Translucent Bubble (Self-explanatory)” was taking place: musicians, dim keyboard-prodding shapes, played space- age boogie from the interior of a pillow-shaped inflatable device that completely filled the stage. The music blipped and burped as colored lights throbbed smearily through the semi-transparent plastic and the audience reclined, chatting, in a state of mild disenthrallment.

“I don’t know,” muttered Boyer. “The bubble thing. Is it working? These things always seem like great ideas to me, but then….”

Boyer, who had organized the event to raise funds for his Jamaica Plain-based self-publishing outlet, Mutable Press, really had nothing to worry about. Thus far, the evening had been a complete success: We had seen a chivalric duel fought with swords by the light of a disco ball, and watched in wonder as a bearded young man calling himself Animal Hospital sat in a nest of drums, guitars, mixers, and recording equipment and constructed, track by looped track, a multi-instrumental jam of considerable beauty. Underground legend Puppet Master Jake appeared before us sans puppets and urbanely shared some tales from his time with the circus (“just prior to my mental breakdown”). As a bonus, the event had drawn a nice-sized crowd of vivid young loft-dwellers, their hair brushed in interesting directions and their laughter honking and incestuous. Art and Mammon, it seemed, had both been served. Boyer, who has performed stories at the Children’s Museum (accompanied by a drummer) and published a manifesto featuring screeds from “ten modern individuals,” is a bohemian all-rounder. He represents, with some aplomb, a faction of this city’s counterculture that is busily whimsical, constantly expressive, and unafraid to go public with its art-overdosed hijinks.

On the merchandise table at the Coolidge–and at the core of the evening– sat copies of Mutable Press’s latest publication, a volume by Boyer entitled “Seven Nights in the Bedroom: A collection of plays from, and memoir of, Bedroom Theater.” Bedroom Theater, initiated in 2002 but currently on hold, is–so far–Boyer’s greatest conceptual coup. Defined in the book as “a bunch of people sitting on my floor and in my bed, while we do readings of original material to much applause and general chafing,” it combines a keen experimental edge with the mammal warmth of a slumber party. Audience/performer boundaries are abolished, and moments are shared on a mattress.

“Seven Nights In The Bedroom,” through reportage and mangled autobiography, chronicles the phenomenon in some depth, providing what will surely be the only printing of plays like Leah Smith and Katya Gorker’s “The Secrets of the Swans” and Boyer’s own “They’re Crying Tears of Fire.” As literature the book is not quite to be recommended, zig- zagging as it does between the bombastic (“I state daily that I am lost and will not be found, because my brothers and sisters have become simply ground beef. . .”) and the geekily, gunkily private (“It was then that Meg showed me the chair-with-wings tattoo that she had on her tailbone, and my eyes went to soup.”)

But then being literary is beside the point. Boyer’s ungainly, passionate, try- anything writing is a performance in the same spirit as his bedroom dramaturgy, or indeed as the spectacle of two caped and portly duellists circling at sword-point under the flung stars of a disco ball–DIY art, as homely and democratic as a night in a karaoke bar, and with even more capacity for revelation.

Did Boyer’s bedroom become a theater? Did the alchemy occur? Sort of. “Blood was ketchup and ketchup was blood,” he concludes at the end of “Seven Nights in the Bedroom.” “We were jokers with a little bit of the transcendental loser thrown in.”

Chris Fujiwara, sometime movie reviewer for the Boston Phoenix, who first stalked into Boyer’s bedroom with his own radically abridged version (16 pages) of John Webster’s “The White Devil,” gets the last word: “Had these plays been better,” he writes in a testimonial contribution to “Seven Nights,” “they might not have been at all.”