Matt Dube

A.D. Jameson is a pretty much a monster when it comes to corrupting familiar characters, folding, spindling and mutilating existing forms, and generally bankrupting your appreciation of traditional narrative. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

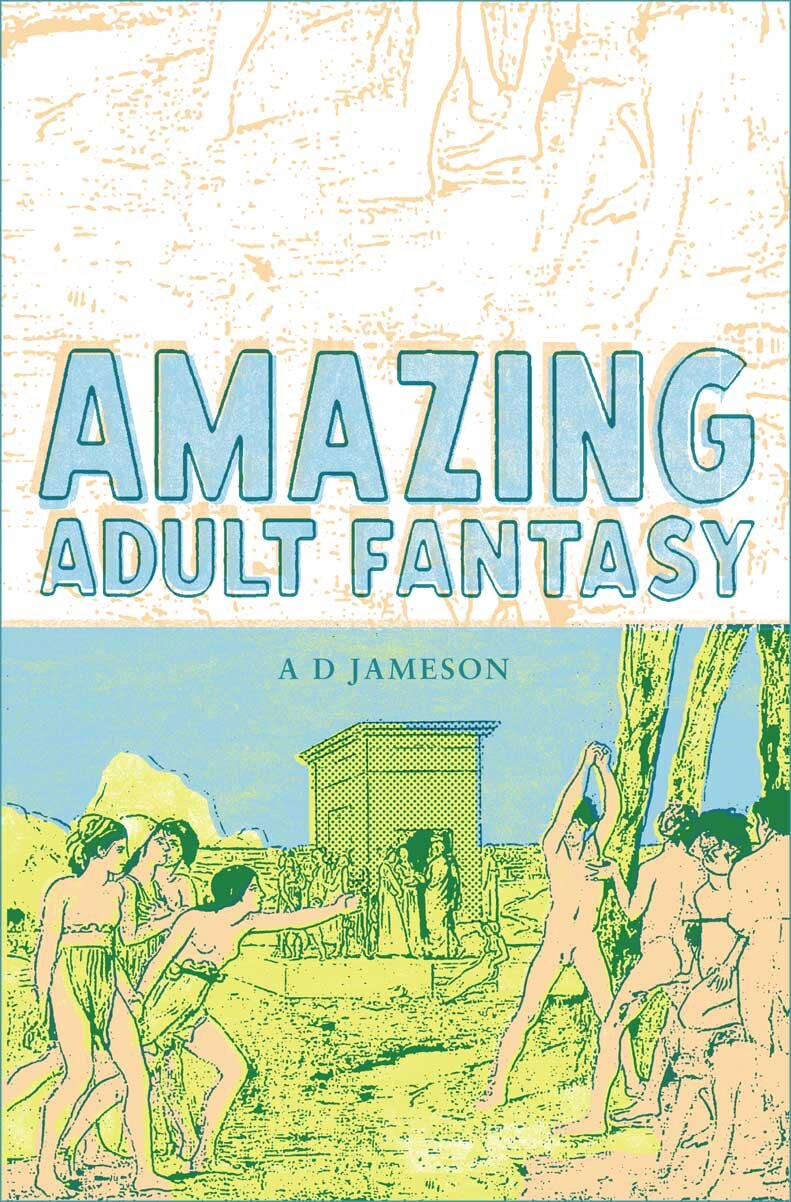

The first half of his short story collection Amazing Adult Fantasy finds him exhuming still-recognizable figures from pop culture and re-casting them in challenging contexts. So, Oscar the Grouch is a misanthrope in a gabrage can, but also the homeless leader of a style of experimental poets and extreme excema sufferer. Likewise, “Our Continuing Mission” exposes the sadness at the heart of the ST:TNG’s snooze-worthy romance between Riker and Troi, and “How to Draw the Thing” is a letter, or perhaps the response to an interview question from someone who might almost be Jack Kirby, or another famous penciler of the Fantastic Four. The best of these narratives sifting through cultural detritus, though, is “Ota Benga Episode Guide: Season Three,” which is formally just what is written on the tin, a series of reference guide-style entries on an imaginary TV show. What elevates this story above the others, though, is the way the fantastic elements of the story (talking monkeys, a ghostly kangaroo with a flaming halo) leaves room for Jameson to revisit and comment on our relationship to the real story of pygmy Ota Benga, a story that does raise the hair on your arms: here,as in other stories Jameson indicts readers as consumers, but also shows the way our conventional narratives distort the very real people at their center. More than squint-eyed fan fic, ”OBEG:ST” recreates empathic dignity for its devalued subject in a way that’s breathtaking.

The book’s second suite, Solar Stories, is, appropriate for such a parallax collection, obsessed with the moon, these stories slice and dice a different model from the one interrogated in the first suite. Where the fan fics recall Barthelme’s verbal impersonations of bureaucrats in love, the language in these longer stories is flatter and almost schematic (“Displaying a scary passivity, Alba wanders out into the desert. Obsessed by caves, she enters a cave and goes spelunking” (98)), which suits their combinatorial approach. Each story introduces a group of characters (often a quartet, but sometimes more, sometimes less) and then poses them in every combination to see what happens. The method invites the kind of deliberate exhaustion Beckett courted ca. Endgame, and Jameson probably shares that writer’s intent: to wear us down, to make us repudiate faith that we can find personal meaning through stories. It’s not for nothing that the book opens with “Fiction” and ends with “Amazing Adult Fantasy,” two somewhat gnomic comments on fiction: “The 21st Century ought to see better fiction, or none at all” (1) and “our stories, we have to admit, have been the cause of all our problems” (164). And yet, Jameson is still writing fictions. I for one hope to read more, especially those that come when Jameson moves beyond dismantling the fictions of the past and begins crafting stories he feels are worthy of the 21st Century.