[This week we thought we’d share an interview with artist, Dominique de Varine, who calls Brittany home, but who we met in the Tibetan colonies of Northern India. Dominque’s answers have been translated from the French. You can find the original French at the bottom of this essay.]

*

Mutable: I think a good place to start our conversation is Dharma and Karma, as this was where our conversation began. What is the relationship between Dharma and Karma in your work? Has it always been this way or has their relationship evolved over time? And also, was there a time when these concepts were not important to your work and some moment when they became more so?

Dominique de Varine: Karma, Dharma, I don’t really know what it is. My ideas are fleeting, they fade with time. When I began my work on the Galipettes series, the question that series seemed to me to be answering was this issue of emptiness. Over time, the echo of fullness invited itself to the point of playing equal with emptiness, and as a dialectic. A reading is complementary to it, to be grasped from the side of reality since it is from this material that my research is ultimately made, and simultaneously to be grasped from the side of the order of the narrative, since reality only exists in relation to the form that we lend it. This narratological order can be pointed out from the opposition between engagement (narrative) and disengagement (narrative). The void, disengagement in the here and now. The fullness, engagement with all the shaping of the world. From there, Dharma and Karma.

M: How have Buddhist concepts in general informed your work over your career and how have they not?

DdV: I have been reading Buddhist texts, often Tibetan ones, since the end of my adolescence. I have always done so, sporadically, with a certain capacity for forgetfulness. I seem to remember that Tibetan Buddhism conceives of sixteen forms of emptiness. The weeks I have just spent, somewhat by chance, rubbing shoulders, closely or from afar, among so many monks counterbalanced by the wild presence of so many monkeys, and with the Tibetan exiles of northern India and the Indian population, at the foothills of the Himalayas, have been a slow process of clarification for me.

M: In what order?

DdV: I was struck by the revelation of something vibrant, something buried, a quality perhaps, something profoundly Buddhist and which was at work in my art. I am not only talking about my creative research but also my semiotic research. My life as a Westerner had hidden this from me. I had no idea how much this attraction to Buddhism had perhaps infused and worked the roots to this extent. I found myself faced with this hypothesis. However, I do not think I am a Buddhist artist any more than I am a semiotic artist. I do not think so. I mean that I have never really planned the “work” as they say, and the “work” after, in terms of specific research. Planning is not my thing. To tell the truth, I do not have the feeling of ever having looked for anything. I have always let things come.

M: What other ideas do you bring to your work? How do they relate to ideas like Karma and Dharma?

DdV: The life of forms has always interested me, from primitive worlds to contemporary societies, that’s my first training. I didn’t go to art school, I’m a semiotician, and the theoretical background came from that. The so-called Paris school of semiotics, developed around the work of A.-J. Greimas, is at the crossroads of linguistics, anthropology and phenomenology. It is structural in essence, which is also a bridge with the Buddhist approach to the conditions of existence. Another influence was Guy Debord’s critique of the Society of the Spectacle. But neither Buddhism nor Guy Debord was discussed at Greimas’ seminar, and these three poles of influence remained dissociated.

M: How did you get started on the path you are on now?

DdV: The artistic vocation gradually imposed itself, nourished by my encounters and my wanderings. I looked with curiosity and without too much judgment, from street painting to the Renaissance chest of drawers, from nature to consumer objects. I don't know where this magnet for the avant-gardes of all persuasions comes from, they spontaneously attracted me very early on, from Malevich to minimalism and Donald Judd, from Arte Povera to Marcel Duchamp. They didn't interest me so much on the theoretical level, to which I remained relatively impervious for a long time, as on the perceptual level. Look. In their approaches to the living, there is in the avant-garde movements an attempt to push the pawn, an idea of surpassing, of “exploring,” of “searching” for reality, of abolishing certain boundaries, which make them markers. To which certain contemporary research echoes.

M: You have spoken of nature and culture. Could you go further into these concepts and how they inform your work?

DdV: This interest in radicalism has always been counterbalanced by my love of the so-called primitive arts, in particular the statuary of the Hopi Native Americans and the wool and wax painting of the Huichole Indians of the Mexican mountains. By my reading of anthropologists, Claude Levi-Strauss, Philippe Descola, James C. Scott. By my visits to the old Guimet museum before the renovation, the great Parisian museum for Asian arts, extraordinary, timeless, shining with a thousand vapor-bursts. For me, this attraction to radicalism and this love of forms considered by some as non-current go hand in hand. Although these art forms are not of the same nature, the avant-gardes as well as “non-current” cultures are perhaps not as far apart as one might think. Both have this in common that they proceed from an exploration of the life of forms, that is to say of reality, of a body, individual or collective, in action, in the world. Exploration of the life of forms which has autonomy and perfection as its bias, posing, dialectizing, pushing the values of nature and culture.

© Seymour Chase Dugowson

M: Then a question. In general, where would you place yourself as an artist?

DdV: I don’t know. It was easier when the notions of radicalism or avant-garde made sense. These notions are now outdated, partly linked to the same sun, modernity. One of the satellites of this sun is the art market. Another is the actuality of the art. Another is a kind of subjection to something rather vague, deeply anthropological, which aspires to become the sun in place of the sun, an idea, latent, hidden, and as if coming to inform everything, the Aim of the artist. Today, but is it so new, the words art and artist are rigged, they no longer correspond to much. Society is too standardized, it has made them into drawer words. In any case, when a fisherman goes to catch trout, is he called a fisherman?

M: Should one resist the art market?

DdV: I don’t feel very concerned. But resisting the art market is confining. Or becomes a matter of fighting for survival; or even positioning. It is sometimes paid for by life paths that contradict the writings or readings of youth. It is better to play with it, to be part of it perhaps but not to be born from it, at the very least, to keep a certain distance. Who still buys art for art’s sake anyway? That may be the crux of the problem. It is not insignificant that bourgeois apartments are empty, now dressed with more or less trendy posters, screens and bland objects, labeled as average international good taste. The excess of digital consumption is part of it. Today people seem lost, as if they had lost taste, or as if they had lost the right to it. And as if a tight framework of verticality prevented them from doing so. So few individuals seem to think and affirm what we call taste.

M: How would you describe the French art scene currently?

DdV: I am intrigued by the fact that so many artists who nourish me and give this rare impression of living their art are located outside the institutionalized circuit of art. There is a fairly clear break between the proliferation of large private or public institutions, which is an essentially Parisian phenomenon, and the state of advancement of art.

M: Is there anyone who stands out as especially interesting?

DdV: To name just a few, I am sensitive to the burlesque alchemy of a Pierrick Sorrin, to the lunar scientifics of Thomas Lanfranchi, to the chic feminism of Claire Maugeais, to the poetic and political mysticism of Benoît Pingeot, to the chromatic research of Xavier Goupil. And then the Chauvet cave. 34,000 years old, twice as old as Lascaux. There is a Chauvet mystery, invented, as archaeologists say, at the very end of the twentieth century, so fertile and so rich in creations. For many, Chauvet constitutes a point of acme due to its extreme sophistication. It is also, mysteriously and as if by a magician's trick, a sorcerer or conjurer, with a powerfully armed irony, what we know as on the one hand the oldest, and on the other hand the most remarkable in terms of pictorial representation and approach to space. At Chauvet, the edge line of the drawing plays with the void in an unequalled dialogue. And then this profession of faith of those who had the privilege of visiting it: that it seems so fresh that the painter could have just gone, or still be there, at that moment hidden behind a rock. At Chauvet, the real, the cosmos, the rock, the animal, the volume and the constantly changing point of view are one.

M: You seem to be discussing the notion of art itself. Can you come back to this idea?

DdV: We should take the codes and melt them from the inside. The word Man was invented, to mean man, woman, child and god. The word art was invented and the word artist. These notions have not always existed and do not always exist. I do not know if the artists who interest me are artists. Yes, certainly, but after? They are not from this pro-active time. It is also that the stakes have shifted. Artists, curators, institutions, critics, the public, collectors, some have sought the new positioning, in a global context where the feeling of exhaustion given by modernity is to be put in parallel with the feeling of environmental, climatic and democratic urgency. Art for art's sake has been cast aside. But an artist’s oeuvre unfolds in time, where it takes on its true scope, and by extension its vision may very well find itself in retreat. Beyond that, the emergence of Asia in the art market, particularly India and China, have systematized its integration within the value of the larger market, in competition with the latest Vuitton bag or the latest fashionable car. Hence the temptation for some to commodify the artist. Even the very forms of social control: bridges have been blown between a roadside radar and certain forms of art.

M: What is art for, according to you?

DdV: Art, including in its political spirit, is to be distinguished from the effect from which it cannot however be dissociated. The risk with the exploration of the effect, in particular of the forms of enunciation, is to slowly, imperceptibly, switch to the viewing of art as the decoration of this reality. Then we forget that art also opens up to something else. It perhaps serves to inform reality, literally: to participate in its shaping.

M: How does your childhood fit in with your art?

DdV: I remember trying things out as a teenager and getting a shock from the depths of my Breton cabin the day I learned that art schools existed, something my old-school aristocratic parents with their foot in the modern world put a welcome brake on. They never stopped me from doing anything again, even Blue Oyster Cult at full blast in my room above theirs. I arrived in Paris a gleaner and spotty, a virgin, a little anxious, lost, outside the norm, unsure of myself and stuttering, in a Latin Quarter that was blowing out its last embers. I made my first friends and they were artists. I quite quickly, against my shyness, started going to galleries, the little scene that was growing at the time. began to experiment, and it evolved into something like minimalism. And then, a few years later, from a sort of dream, after six months, a Galipette emerged. It took three weeks for the idea of remaking Galipette to finally impose itself by chance. Then came the idea, unfolding slowly and like a morphogenesis, the seed going to the tree, of the principle of the series. It is a mental and physical experience, a strange sensation, a souvenir today. But always, pardon me for being poetic, lying down without knowing it at the foot of this tree, I taste its fruits. I forgot for a long time that all this, the formal diversity that this work takes, starts from a simple sheet of A4 paper, blank, pierced with emptiness. The great shyness that for a long time made me stutter and blush more than was necessary very slowly faded. I began to show my work, and to tell myself that the game was not won. And then, after a few years, I heard that I had already been doing squares for some time, as Piet Mondrian understood his horizontalities and verticalities. Many focus on the square, which is only one element of the general syntax. One thing is what happens in and outside the informed square, another is what happens in and outside the rectangle informing the work.

M: In your work, what is the relationship between square and rectangle?

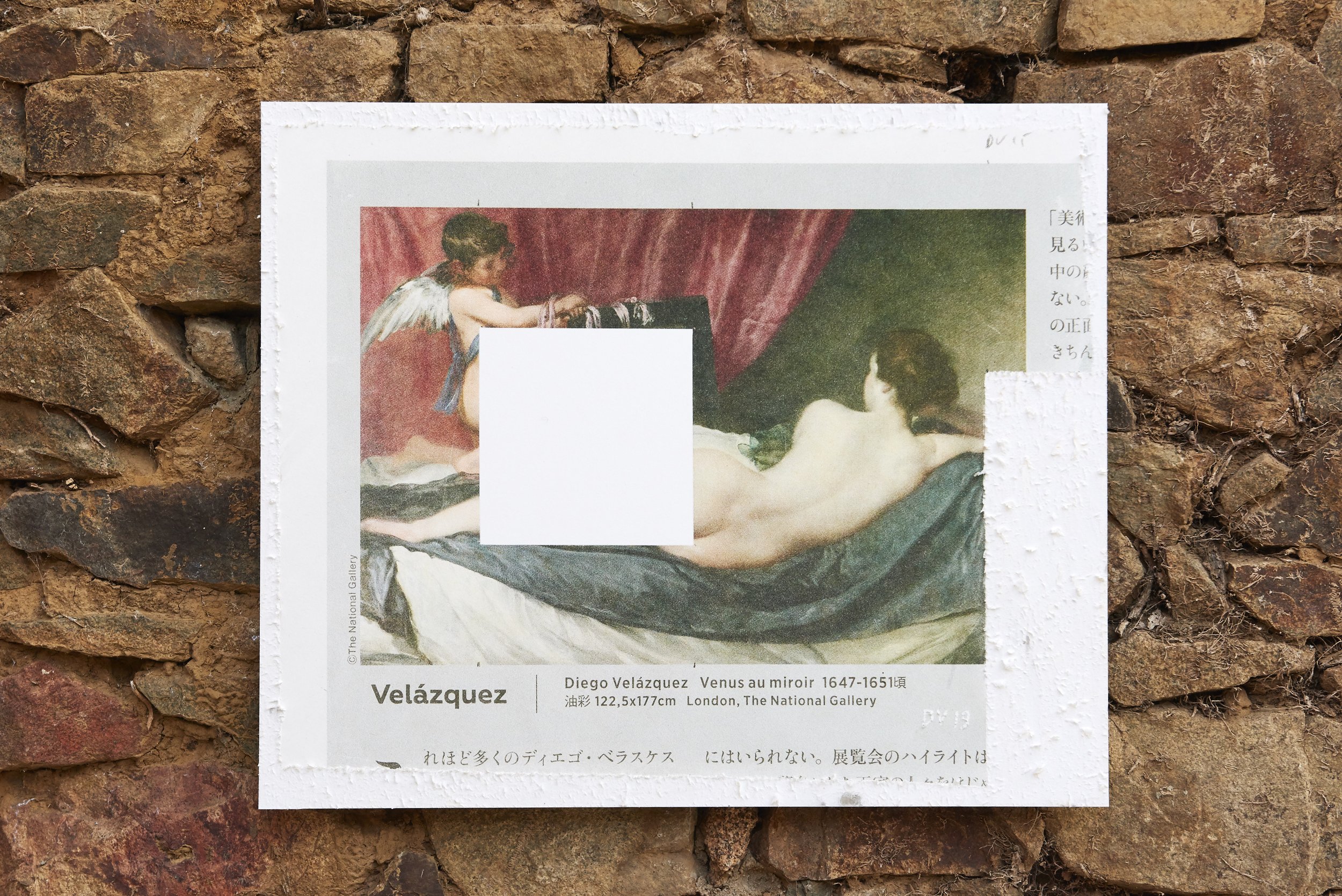

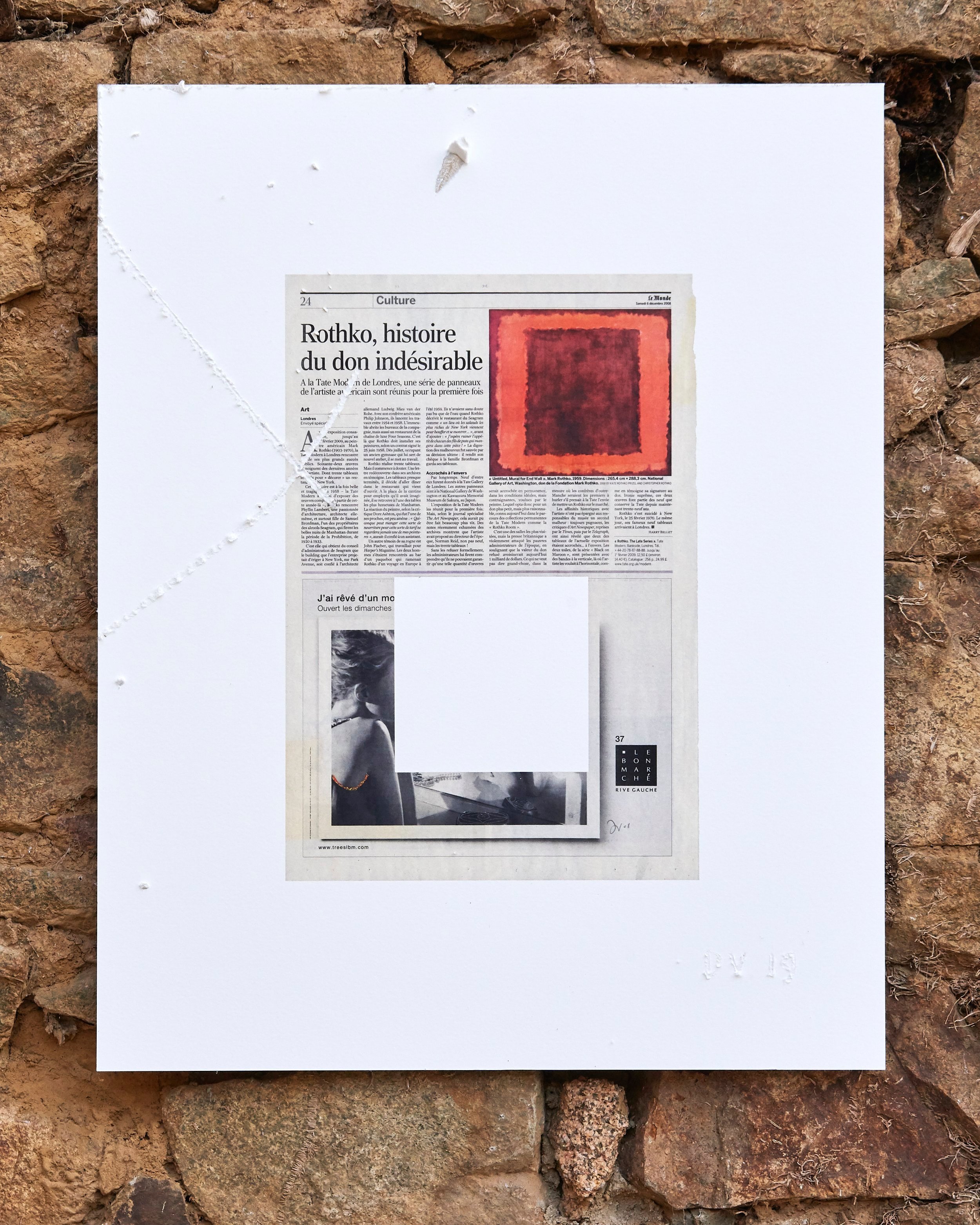

DdV: From an object taken from the course of things, samsara in its perpetual renewal, a blank or already painted painting, a piece of paper (often newspaper), a box of chocolate, a piece of rock, an industrial object, etc., I take or introduce a rectangular surface. I extract from this surface, by means of the square, a resonant material: simple subtraction, absence, a slightly alchemical path. Exactly as in yoga, the idea is to stabilize. It is important to understand that the rectangle is taken from the world, not artificially like a painting to be painted, but like a potential painting already there, to be picked and realized in a square.

M: What is the relationship of the squares to the artwork as a whole? Does it change from one composition to another?

DdV: The square is not an insignificant form, being the most direct, the finest and the simplest expression to synthesize the idea of culture. Hence, also, the black quadrangle, not really square, of the great anchor Kasimir Malevich. But the quadrangle does not come from nowhere, it comes from Malevich's reflections on the nature of the rectangle, in particular from the association he makes with modernity, which he pushes to surpass. Hence, also, the almost square (or not really rectangular) paintings of Robert Ryman. Or, again, the mise en abymes of Josef Albers. They go there to see like poets, and with their painter's tools. In your poet's laboratory with your brushes and your colors acting as microscope you pose your equation and your equation tells you square = culture, with this latent association between culture and immanence. They, that is where they start from, they approach the square and question it. We can also note that the approach to the square seems to have color as a corollary, and from the exclusive angle of monochrome. White and black, on the edges of color, in Malevich; the initiating white in its multiple shades in Ryman; the multiplicity of shades, organized by square flat areas of color in Albers, who is also a theoretician of color.

M: And in your work?

DdV: Color and square are separated. Color comes from micro series, neon, colored pencils, fabric, etc. My research here is exclusively magnetic, including the series of flags, according to a structural approach to color.

M: What about the square?

DvD: It is precisely a square, even if I sometimes allow myself a certain unknown. I annihilate the rectangle into a square, I pierce the square and go see what the champagne bubble does on the surface. People sometimes think that I make squares, I answer that I make rectangles. The question is not so much the square as the rectangle that accommodates this square: where does this rectangle come from, what function has our Western world given it that often still remains so transparent? Marcel Duchamp said of painting (and of the painting) that it has a delay effect. I think he meant life. It seems to me that this question of effect is a driving force behind my work.

M: How are the square and the rectangle concretely linked?

DdV: They are concretely linked to each other according to a relationship of subtraction. The plasticity of the system is quite great and its modes of realization multiple. But above all, this system induces with regard to the void (the "square informed") a principle not so much of equivalence as of vibration, a dynamic perspective linking the rectangular "informed" to the square "informed". This creates a kind of logic in disengagement of the category of immanence.

M: How would you explain your work to an art student, an alien, a child?

DdV: To an art student, I ask to observe the effects of decantation like a winemaker; to an Alien I ask if we are in agreement; to a child, simply to look and remain deaf to any sort of explanation.

_________________________________________

[Original French Transcript found here:]

Mutable: Je pense que le Dharma et le Karma sont un bon point de départ pour notre conversation, car c'est là que notre conversation a commencé. Quelle est la relation entre le Dharma et le Karma dans votre travail ? Est-ce que cela a toujours été ainsi ou leur relation a-t-elle évolué au fil du temps ? Et aussi, y a-t-il eu un moment où ces concepts n'étaient pas importants pour votre travail et un moment où ils l'ont devenu davantage ?

DdV: Le Karma, le Dharma je ne sais pas trop ce que c’est. Mes idées sont fugaces, elles s’estompent avec le temps. Quand mon travail de la série des Galipettes a commencé, la question qui m’a semblé pouvoir en répondre était celle du vide. Avec le temps l’écho du plein s’est invité jusqu’à faire jeu égal avec le vide, et comme dialectique. Une lecture lui est complémentaire, à saisir du côté du réel puisque c’est de cette matière là qu’est finalement faite ma recherche, et simultanément à saisir du côté de l’ordre du récit, puisque le réel n’existe qu’en regard de la forme que l’on lui prête. Cet ordre narratologique, on peut le pointer à partir de l’opposition entre embrayage (narratif) et débrayage (narratif). Le vide, débrayage en ici et maintenant. Le plein, embrayage à toutes les mises en forme du monde. De là le Dharma et le Karma.

M: Comment les concepts bouddhistes en général ont-ils influencé votre travail au cours de votre carrière et comment ne l’ont-ils pas fait ?

DdV: Je lis des textes bouddhiques, souvent tibétains, depuis la fin de mon adolescence. Je l’ai toujours fait, de loin en loin, avec une certaine capacité à l’oubli. Je crois me souvenir que le bouddhisme tibétain conçoit seize formes du vide. Les semaines que j’ai passé, un peu par hasard, à côtoyer de près ou de loin tant de moines, présence contrebalancée par celle, sauvage, de tous ces singes, et avec les exilés tibétains du nord de l’Inde et la population indienne, au pied de l’Himalaya, ont été pour moi une lente décantation.

M: De quel ordre ?

DdV: J’ai été saisi par la révélation de quelque chose de vibratile, d’enfoui, une qualité peut-être, de profondément bouddhique et qui était à l’oeuvre dans mon travail. Je ne parle pas seulement de mes recherches plastiques mais aussi sémiotiques. Ma vie d’occidental m’avait caché cela. Je n’avais pas idée de combien cette attirance pour le bouddhisme avait peut-être infusé et travaillé à ce point les racines. Je me trouvais face à cette hypothèse. Pour autant, je ne pense pas être un artiste bouddhique pas plus que je ne suis un artiste sémiotique. Je ne pense pas. Je veux dire que je n’ai jamais trop planifié l’« œuvre » comme on dit, et le « travail » d’après, en des termes de recherche spécifique. La planification n’est pas mon truc. À vrai dire, je n’ai pas le sentiment d’avoir jamais cherché quoi que ce soit. J’ai toujours laissé les choses venir.

M: Quelles autres idées apportez-vous à votre travail ? Comment se rapportent-elles à des idées comme le Karma et le Dharma ?

DdV: La vie des formes m’a toujours intéressé, des mondes premiers aux sociétés contemporaines, c’est cela ma première formation. Je n’ai pas fait d’école d’art, je suis sémioticien, et le bagage théorique est venu là-dessus. L’école sémiotique dite de Paris, développée autour de l’œuvre de A.-J. Greimas, se trouve à la croisée de la linguistique, de l’anthropologie et de la phénoménologie. Elle est d’essence structurale, ce qui est aussi un pont avec l’approche bouddhique des conditions d’existence. Une autre influence a été la critique de Guy Debord de la société du Spectacle. Mais on ne parlait ni de bouddhisme ni de Guy Debord au séminaire de Greimas, et ces trois pôles d’influence sont resté dissociés.

M: Comment avez-vous commencé à emprunter le chemin que vous suivez actuellement ?

DdV: La vocation artistique s’est imposée progressivement, nourrie de mes rencontres et de mes errances. J’ai regardé avec curiosité et sans trop de jugement, de la peinture de rue à la commode Renaissance, de la nature aux objets de consommation. Je ne sais d’où me vient cette aimantation pour les avants-gardes de toutes obédiences, elles m’ont très tôt spontanément attiré, de Malevich au minimalisme et à Donald Judd, de l’Arte Povera à Marcel Duchamp. Elles ne m’ont pas tant intéressé sur le plan théorique auquel je suis longtemps resté relativement imperméable que sur le plan perceptuel. Regarder. Dans leurs approches du vivant, il y a dans les mouvements d’avant-garde une tentative de pousser le pion, une idée de dépassement, d’« explorer », de « chercher » le réel, d’abolir certaines frontières, qui en font des marqueurs. Auxquels certaines recherches contemporaines font écho.

M: Vous avez parlé de nature et de culture. Pourriez-vous approfondir ces notions et la manière dont elles influencent votre travail ?

DdV: Cet intérêt pour la radicalité a toujours été contrebalancé par mon amour des arts dits premiers, en particulier de la statuaire des amérindiens Hopi et de la peinture de laine et de cire des indiens Huicholes des montagnes mexicaines. Par ma lecture des anthropologues, Claude Levi-Strauss, Philippe Descola, James C. Scott. Par mes visites au vieux musée Guimet d’avant la rénovation, le grand musée parisien pour les arts asiatiques, extraordinaire, hors du temps, brillant de mille éclats-vapeurs. Pour moi, cet attrait pour la radicalité et cet amour de formes considérées par certains comme non-actuelles vont de pair. Bien que ces formes d’art ne soient de même nature, les avant-gardes autant que les cultures « non-actuelles » ne sont peut-être pas si éloignées que l’on croit. Les unes et les autres ont ceci de commun qu’elles procèdent d’une exploration de la vie des formes, c’est-à-dire du réel, d’un corps, individuel ou collectif, en acte, en monde. Exploration de la vie des formes qui a pour parti-pris autonomie et perfection, posant, dialectisant, poussant les valeurs de nature et de culture.

M: Alors une question. En général, où te placerais-tu en tant qu’artiste ?

DdV: Je ne sais pas. Cela était plus facile quand les notions de radicalité ou d’avant-garde faisaient sens. C'est notions-là sont aujourd’hui périmées, en partie liées à un même soleil, la modernité. Un des satellites de ce soleil est le marché de l’art. Un autre est l’actualité de l’art. Un autre est une forme de sujétion à quelque chose d’assez flou, profondément anthropologique, qui serait devenue soleil à la place du soleil, une idée, latente, cachée, et comme venant tout informer, de Visée. Aujourd’hui, mais est-ce si nouveau, les mots art, artiste, sont pipés, ils ne correspondent plus à grand chose. La société est trop normée, elle en a fait des mots-tiroirs. De toute façon, quand un pêcheur va à la truite, est-ce qu’il se nomme pêcheur ?

M: Il faut résister au marché de l’art ?

DdV: Je ne me sens pas très concerné. Mais résister au marché de l’art, cela enferme. Ou devient affaire de lutte pour la survie ; ou encore de positionnement. C’est parfois payé de parcours de vie en contradiction avec les écrits ou les lectures de jeunesse. Il vaut mieux d’en jouer, en être peut-être mais ne pas en naître, à tout le moins, garder une certaine distance. De toute façon qui achète encore de l’art pour l’art ? C’est peut-être cela le fond du problème. Il n’est pas anodin que les appartements bourgeois soient vides, dorénavant habillés de posters plus ou moins branchés, d’écrans et d’objets insipides, étiquetés du bon goût moyen international. Le trop-plein de consommation numérique est passé par là. Aujourd’hui les gens semblent perdus, comme s’ils avaient perdu le goût, ou comme s’ils en avaient perdu le droit. Et comme si une trame serrée de verticalité les en empêchait. Si peu d’individus semblent penser et affirmer ce que l’on appelle un goût.

M: Comment décririez-vous la scène artistique française actuelle ?

DdV: Je suis intrigué du fait que tant d’artistes qui me nourrissent et donnent cette si rare impression de vivre leur art, se situent en dehors du circuit institutionnalisé de l’art. Il y a une coupure assez nette entre la multiplication des grandes institutions privées ou publiques, qui est un phénomène essentiellement parisien, et l’état d’avancement de l’art.

M: Y a-t-il quelqu’un qui se démarque comme étant particulièrement intéressant ?

DdV: Pour n’en citer vraiment que quelques uns, je suis sensible à la burlesque alchimie d’un Pierrick Sorrin, au lunaire scientifique de Thomas Lanfranchi, au féminisme chic de Claire Maugeais, à la mystique poétique et politique de Benoît Pingeot, aux recherches chromatiques de Xavier Goupil. Et puis la grotte Chauvet. 34000 ans, deux fois plus ancienne que Lascaux. Il y a un mystère Chauvet, inventée, comme le disent les archéologues, en la toute fin du vingtième siècle, si fertile et si riche en créations. Pour beaucoup, Chauvet constitue du fait de son extrême sophistication un point d’acmé. Elle est aussi, mystérieusement et comme par un tour de magicien, de prestidigitateur ou de conjuré, à l’ironie puissamment armée, ce que l’on connait d’une part de plus ancien, et d’autre part de plus remarquable en matière de représentation picturale et d’approche de l’espace. À Chauvet, la ligne de bord du dessin joue avec le vide en un dialogue inégalé. Et puis cette profession de foi de ceux ayant eu le privilège de la visiter : qu’il semble tant la fraîcheur que le peintre s’en serait allé, là, à l’instant caché derrière une roche. À Chauvet, le réel, le cosmos, la roche, l’animal, le volume et le point de vue en constante mutation ne font qu’un.

M: Tu sembles discuter la notion d’art elle-même. Peux-tu revenir à cette idée ?

DdV: Il faudrait prendre les codes les fondre de l’intérieur. Le mot Homme a été inventé, pour dire homme, femme, enfant et dieu. Le mot art a été inventé et le mot artiste. Ces notions-là n’ont pas toujours existé et n’existent pas toujours. Je ne sais si les artistes qui m’intéresse sont des artistes. Oui, certainement, mais après ? Ils ne sont pas de ce temps pro-actif. C’est aussi que les enjeux se sont déplacés. Artistes, curateurs, institution, critiques, public, collectionneurs, certains ont cherché le nouveau positionnement, dans un contexte global où le sentiment d’épuisement donné par la modernité est à mettre en parallèle au sentiment d’urgence environnementale, climatique et démocratique. L’art pour l’art est une valeur en déshérence. Mais une oeuvre se déploie dans le temps, là où elle prend sa véritable ampleur, et par extension probablement en retrait. Au-delà, l’émergence de l’Asie dans le marché de l’art, notamment de l’Inde et de la Chine, ont systématisé sa valeur d’intégration, en concurrence avec le dernier sac Vuitton ou la dernière voiture à la mode. D’où chez certains la tentation d’instrumentaliser l’artiste. Jusqu'aux formes même du contrôle social : les ponts ont sauté entre un radar de bord de route et certaines formes d’art.

M: L’art selon toi, ça sert à quoi ?

DdV: L’art, y compris dans son ressort politique, est à distinguer de l’effet dont il ne peut cependant se dissocier. Le risque avec l’exploration de l’effet, notamment des formes de l’énonciation, c’est de basculer lentement, imperceptiblement, du côté de la décoration de ce réel. Alors on oublie que l’art, cela ouvre aussi à autre chose. Cela sert peut-être à informer le réel, littéralement : participer de sa mise en forme.

M: L’enfance de l’art pour toi, cela s’est passé comment ?

DdV: J’ai souvenir d’avoir tenté des trucs, adolescent, et d’avoir pris un choc du fond de ma cabane bretonne le jour où j’ai appris qu’il existait des écoles d’art, ce à quoi mes parents aristocrates vieille école avec leur pied dans la modernité ont mis un frein bienvenu. Ils ne m’ont plus jamais rien empêché et même Blue Oyster Cult à fond dans ma chambre au dessus de la leur. Je suis arrivé à Paris glaneur et boutonneux, puceau, un peu anxieux, perdu, hors des codes, peu sûr de moi et bégayant, dans un Quartier Latin qui soufflait ses dernières braises. Je me suis fait mes premiers copains et ceux-ci étaient artistes. J’ai assez rapidement, contre ma timidité, commencé à fréquenter les galeries, le petit milieu qui montait à l’époque. J’ai commencé à tenter des trucs et cela a pris forme assez minimale. Et puis, quelques années passées, d’une sorte de rêve est sorti au bout de six mois une Galipette. Il a fallu trois semaines pour que l’idée de refaire Galipette finisse par s’imposer par hasard. Alors est venu l’idée se déployant lentement et comme une morphogenèse, la graine allant à l’arbre, du principe de la série. C’est une expérience mentale et physique, une étrange sensation, un souvenir aujourd’hui. Mais toujours, pardon de faire le poète, m’allongeant sans le savoir au pied de cet arbre, je goûte de ses fruits. J’ai longtemps oublié que tout cela, la diversité formelle que prend ce travail, part d’une simple feuille de papier de format A4, vierge, percée au vide. La grande timidité qui m’a longtemps fait bégayer et rougir plus que de mesure s’est très lentement estompée. J’ai commencé à montrer mon travail, et me dire que la partie n’était pas gagnée. Et puis, au bout de quelques années, j’ai entendu que cela faisait déjà un certain temps que je faisais du carré, comme Piet Mondrian l’a entendu de ses horizontalités et de ses verticalités. Beaucoup focalisent sur le carré, qui n’est qu’un élément de la syntaxe générale. Une chose est ce qui se passe dans et hors le carré informé, une autre ce qui se passe dans et hors le rectangle informant l’œuvre.

M: Dans votre travail, quelle est la relation entre le carré et le rectangle ?

DdV: D’un objet prélevé sur le cours des choses, le samsara dans son perpétuel renouvellement, un tableau vierge ou déjà peint, un bout de papier (souvent de journal), une boite de chocolat, un morceau de roche, un objet industriel, etc., je prélève ou j’introduis une surface rectangulaire. J’extrais de cette surface, par le biais du carré, une matière en résonance : simple soustraction, absence, voie un peu alchimique. Exactement comme dans le yoga l’idée est de stabiliser. Il est important de comprendre que le rectangle est prélevé, du monde, non pas artificiellement comme un tableau à peindre, mais comme un potentiel tableau déjà là, à cueillir et à réaliser en carré.

M: Quel est le rapport des carrés avec l'œuvre dans son ensemble ? Change-t-il d'une composition à l'autre ?

DdV: Le carré n’est pas une forme anodine, étant l’expression la plus directe, la plus fine et la plus simple pour synthétiser l’idée de culture. D’où, aussi, le quadrangle noir, pas vraiment carré, du grand ancré Kasimir Malévitch. Mais le quadrangle ne vient pas de nulle part, il vient des réflexions de Malévitch sur la nature du rectangle, notamment de l’association qu’il en fait avec la modernité, qu’il pousse à dépasser. D’où, aussi bien, les tableaux à nouveau presque carrés (ou pas vraiment rectangles) de Robert Ryman. Ou, encore, les mises en abyme chez Josef Albers. Ils y vont voir comme des poètes, et avec leurs outils de peintre. Dans votre laboratoire de poète avec vos pinceaux vos couleurs pour microscope vous posez votre équation et votre équation vous dit carré = culture, avec cette association latente entre culture et immanence. Eux, c’est de cela d’où ils partent, ils approchent le carré et le questionnent. On peut aussi remarquer que l’approche du carré semble avoir la couleur pour corollaire, et sous l’angle exclusif du monochrome. Le blanc et le noir, aux lisières de la couleur, chez Malévitch ; le blanc initiateur en ses multiples teintes chez Ryman ; la multiplicité des teintes, organisée par aplats carrés de couleur chez Albers, par ailleurs théoricien de la couleur.

M: Et dans votre travail ?

DdV: Couleur et carré sont séparés. La couleur procède de micro séries, au néon, aux crayons de couleurs, au tissu etc. Mes recherches sont ici exclusivement aimantées, y compris la série des drapeaux, selon une approche structurale des couleur.

M: S’agissant du carré ?

DdV: Il est précisément carré, même si je m’accorde parfois une certaine inconnue. Le rectangle, je l’annihile en carré, le carré, je le perce et vais voir ce que fait la bulle de champagne en surface. Les gens croient parfois que je fais des carrés, je réponds que je fais des rectangles. La question n’est pas tant du carré que du rectangle qui accueille ce carré : d’où vient ce rectangle, quelle fonction notre monde occidental lui a-t-il donné qui reste encore souvent si transparente ? Marcel Duchamp disait de la peinture (et du tableau) qu’elle est un effet Retard. Je pense qu’il voulait dire sur la vie. Il me semble que cette question de l’effet est un moteur de mon travail.

M: Comment le carré et le rectangle sont-ils concrètement liés ?

DdV: Ils sont concrètement liés l’un à l’autre selon un rapport de soustraction. La plasticité du système est assez grande et ses modes de réalisation multiples. Mais surtout, ce système induit à l’égard du vide (l’« informé carré ») un principe non pas tant d’équivalence que de vibration, perspective dynamique liant l’« informé » rectangle à l’« informé » carré. Cela créé une espèce de logique en débrayage de la catégorie de l’immanence.

M: Comment expliqueriez-vous votre travail à un étudiant en art, à un extraterrestre, à un enfant ?

DdV: To an art student je demande d’observer les effets de décantation comme un vigneron ; à un Alien je demande si on est bien d’accord ; à un enfant de simplement regarder et de rester sourd à toute sorte d’explication.