My friend Bradshaw’s been out of a home for some weeks now. A year or so ago, the owner of the building Bradshaw rented in, in Chicago, was foreclosed upon—and not just in Bradshaw’s building. The owner was held up to a debt in the range of thirty million dollars, spread across many foreclosed-upon properties, and he thus fled to his native Ukraine.

But before he left, he told Bradshaw—earnest, fuzzy Bradshaw, who’s both tragically indecisive and critically critical of all things there are—that the electricity was part of his rent. It wasn’t. The electricity went out weeks before the date the bank was forcing Bradshaw out of his unit (“we want owners, no renters”), and when he called ComEd, they told him that he was a thief, that he ought to pay up his eight-thousand dollars of stolen energy, or turn himself into the police. The bank said it wasn’t their problem, either. Bradshaw vomited for a day, lied in the middle of art school’s tiled floors, and has now stayed many nights in my apartment while getting his things into storage, settling debts, speaking with shark-faced attorneys, and fearing the descent of Chicago’s unchecked vultures, floating their patient circles around his struggling self.

And I’ve got a vulture to worry about, too. After refusing to pay a fifty-dollar “let-in fee” to my “property manager,” I’ve been told that I’m a “douche-bag” by the man, and been forced to sign a new lease with higher rent, but for only two months, while the man “re-evaluates.” I then spend countless hours envisioning his demise, negotiating over his head with the building’s owner, drinking myself into tizzies with the foretold glory of victory over this Napoleonic imp. It’s him I imagine as the one defending me, in my daily solo-sessions at the basketball court, practicing my left-handed hook shots against the air. It’s him I imagine falling, as I rise.

But my hook-shot is still only so good; it can only take me far enough to impress my friends, and maybe some several strangers. In my Art—in the works that flow through my silly, typing-obsessed fingers—perhaps there is more.

“Let’s defeat them,” I say to Bradshaw, one more morning with him on my couch. “Let’s defeat all these vultures, all these insidiously nested, money-eating sloths. Let’s absolutely eradicate them, with our POETRY.”

“Yes,” he replies, “I believe that we should. I believe that we should make naked all of the human-to-human terrorism in the gatekeepers of this city’s livable land. That we should do it with the densest, most viscerally undeniable of mini-tomes.”

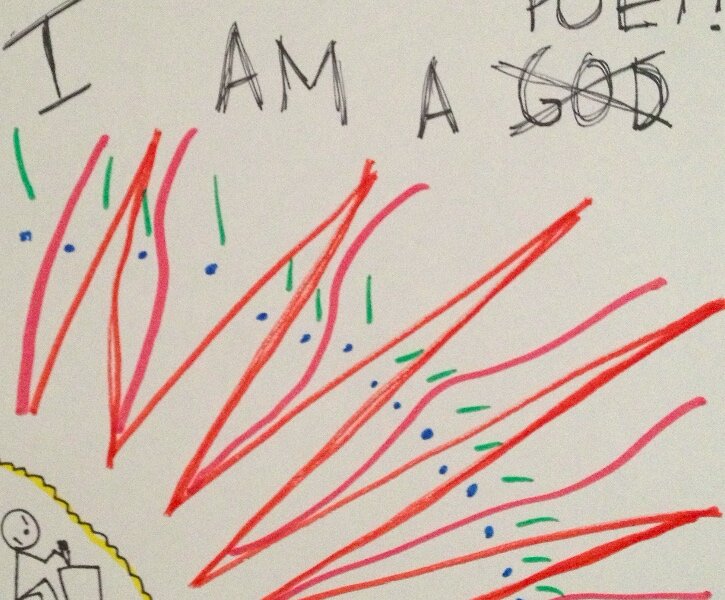

I snatch a drawing pad from the coffee table, and begin to draw the machinations we speak of. And as I draw them, we’re talking about the dystopian bents over-coloring this nation that we live in. We speak of rising prison sentences, for crimes of decreasing significance. We speak of big brother’s eyes on our e-mails about marijuana and occasional violence. We speak of fifty schools closing so that a city can give tens of millions to a private arena, and of the Mayor who says “fuck off” to anyone questioning it. We speak of the futility of saying anything about anything of this. We imagine a fortress of cells, covering the continent, while the crème of the vultures walk atop its golden-spackled roof; their new world’s new ground level, with whatever service from whatever meeklings below, whenever they want it.

I title my work on the drawing pad ‘The Good Guy Gun,’ which shoots all-solving rainbows at the vultures, the lions, the vicious giraffes leering down at our struggles, waiting for the next chance to exploit them.

I explain to Bradshaw how many (hundreds) of steps my paying, desk-job work is removed from what he might understand as a ‘product,’ and wonder how to draw a gun that could solve that problem.

And later in the day I’m alone at a comic book store, snapping pictures of the plush figurines they sell from mine and Bradshaw’s favorite cartoon show, ‘Adventure Time.’

In the show, we’re taken by the hand of a boy’s rosy and perverse imagination; he travels with his super-powered dog, picaresquely solving problems and quashing villains in what is (we see in hints, when the show’s creators want us to) actually a broken, post-apocalyptic slab of barely-life.

We draw, we write, we speak, we laugh and dance our ways around everything that can remind us of our powerlessness, of how indomitable our ceilings really are. We practice and practice the product-estranged work processes most equivalent to left-handed hook-shots, too—because specialists are valuable, because specialists might even get a coin or two of the gold from the snarling giraffes, in this wreckage that they’ve made for us.

We dial into our laptops, and find even more roads of dysfunction and doom, in the world around us, in all of everything that we read. We download films that remind us of nothing, we scheme our intoxicating maps through the shit.

John Wilmes is a writer and professor in Chicago, and the author of Jad's Dad Milo, available at Mouse House Books.